Unnecessary Blackness in the Pipeline

Rahiem Shabazz is more than just your average documentarian. He is a well-educated film maker that has placed a spotlight on a lesser known process plaguing our schools. Take a look at what he has uncovered in his research and his plans for the future.

Corletha: Rahiem, I’m pretty sure that the large majority of our readers know who you are, but, for those that may not, can you tell us about who, Rahiem Shabazz is?

Rahiem: Who, Rahiem Shabazz is; I hate describing myself. Sometimes I don’t even believe [it] when other people describe me. Sometimes I sit back in amazement and say, wow! I’ve come a long way! Nevertheless, Rahiem Shabazz is an individual born and raised in Harlem. I like to say that I come from the unruly streets of Harlem. At a young age, like many of my peers, I found myself on the wrong side of the law and, the result of that led to my incarceration. While incarcerated, I began to see life different. I began to see life through a different lens. I always was an avid reader and Marcus Garvey was somebody that I read every one of his books; every writing. One of the things he said in his books is, “intelligence rules the world and ignorance casts a burden.” So I never wanted to be a burden to my people.

While I was incarcerated I went to college and I graduated eight days before I got released. I graduated the top five percent of my class. While I was in college, everybody told me I was a prolific journalist; that you know, that my writing was phenomenal. So, when I came out, I started my journey as a hip-hop journalist. I have written for pretty much every urban driven magazine. If I didn’t write for them, they probably wanted me to write for them but they weren’t cutting a big enough check. I did that for a couple of years. As a writer, you know anything that has to do with the written word, I have a grasp on that.

You know, while I was locked up I wrote a script called The Sun Will Rise. That particular script: I got out, I was moving around, I was using my industry contacts and I was trying to sell that. I got a lot of good offers. Well I got a lot of offers; I am not going to say good offers. The offers that I did get, I wouldn’t have been able to get my clothes out of the cleaners with that type of money. So, I turned down all of the offers. I raised enough money myself and I shot it as a short film. To make a long story short and short story even shorter, the end result was I began to win seven different awards.

One of those awards was from the Atlanta Hip Hop Film Festival and I was the last to be apprenticed for about 3 days on the set of Daddy’s Little Girls with Tyler Perry’s studio. On the third day, I approached the executive producer. His name was Roger Bob. I talked my way into getting a job on the set and did that for a little while. I worked on 4 films. In between time, I was doing promotional and music videos and different things like that. Then, I wanted to step out on my own. I wanted to do things that were near and dear to my heart. So, I went back to a proposal that I had written.

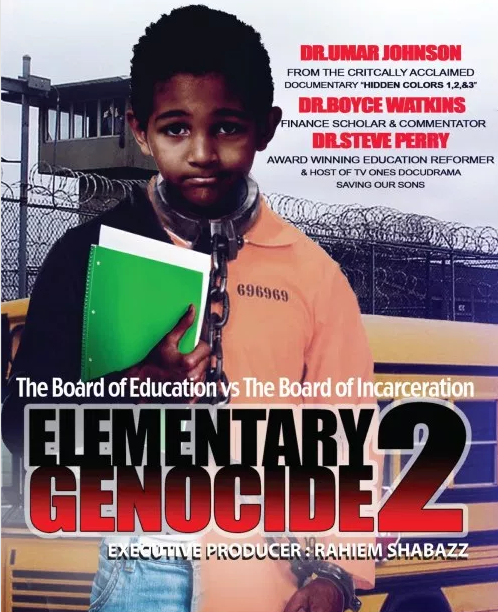

For college, we all had to write a proposal for a non-profit organization. One of them was on urban education and on the school to prison pipeline. So that was the basis for me to do the documentary and further research. I didn’t know it was going to be as big as it has gotten. And low and behold, I released it. The first one is called Elementary Genocide: School to Prison Pipeline. It deals with how the government and the school system looks at the reading scores of fourth and fifth graders; to be able to determine how many prisons they are going to build within the next ten or fifteen years. Then, they look at those numbers and sell those prisons on the stock market.

So that was the first one that led to the second one, which is Elementary Genocide 2: The Board of Education VS. Board of Incarceration. . With that one, we wanted to go back to the landmark ruling of Brown VS. The Board of Education and we wanted to ask the proverbial question, “Has integration done us more harm than good?” We know it done us more harm, as the result of what we are seeing today. Last but not least, I did Elementary Genocide 3: Academic Holocaust. Academic Holocaust talks about the assassination of your mind, the assassination of critical thinking.

It’s no different than the killing of black bodies that is happening by state execution race soldiers in the United States. That in conclusion, that’s who I am. I like to refer to myself as a social justice activist with a camera. So, a lot of my films reflect what is going on in society. I am not just a documentarian. I am a film maker. I’m primarily known for my documentaries, but in the future, I want to be known for some other things. Like full feature films and you know, romance comedies and different things like that. TV shows and so I got a lot of things that I want to work on.

Corletha: In that, you mentioned briefly about working in Tyler Perry Studios, is that what brought you to Atlanta?

Rahiem: No. That didn’t bring me to Atlanta. I had did 2 years of parole in New York City. I just got off parole and it was one of those situations. I had to decide. You know, because I knew that I didn’t want to work for nobody. I knew I had to position myself to be my own boss. So I knew with the writing, I could freelance. I could be wherever I wanted to be. As a writer, you want to be in a conducive environment. I felt Atlanta was that market that would offer me that. After working with Tyler Perry, I haven’t worked a traditional job or worked for anybody in the last ten years. So, everything was strategically planned.

Corletha: That’s amazing. That’s absolutely amazing. When it comes to your documentary series, why in particular the name, “Elementary Genocide”?

Rahiem: Elementary because it starts with the elementary aged students in school. Genocide is the particular killing of a race of a people. Whenever you look at the word elementary, you see the word element; so we are dealing with the 4 elements of life. Like I said, genocide dealing with the killing of the generation of people. But you know when I put out the documentary, after I came up with the name, I was doing further research. The first documentary brought me all around the world; doing screenings everywhere. One of the things that people was saying everywhere is that it focused a lot, primarily on young boys. What about the young girls? So, I had to go back and do more research. So that is what made me want to do number two. We found out that there was an 800% increase in the last 30 years of incarceration of females. I also learned that the school to prison pipeline begins the first day that an African American boy or girl sets foot in a kindergarten class. They can track it by the time they are in the third grade by their reading scores. I found that out, after the documentary was released. If I would have found that out [before], I probably would have had another name. I probably would have had Preschool to Prison Pipeline.

Corletha: Alright. And I have heard you make mention of a few key elements, particularly when an African American child enters kindergarten, this tracking begins. Are you able to give a brief description of the school to prison pipeline, how it works, what are some things to look out for, things of that nature?

Rahiem: Oh absolutely. There are so many different scenarios, cases, instances that, I wouldn’t know where to begin. Oh, I will begin with this one. They have a thing called willful defiance. And that essentially is the teacher telling you to sit down; and you saying, ‘why I got to sit down?’ But you do go and sit down. But you don’t sit down as fast as she would like you to, and you question her authority. That can get you sent to the principal’s office. That can get police officers coming into the class, physically removing you and when they do that, they give you a charge of assault.

We have seen instances where a child brought a nail clipper to the school was arrested for having a weapon. Kindergarten students were arrested for kissing another kindergarten student. One child dealt with charges of sexual harassment for telling the teacher that she was cute. There are so many different incidents. Another example, a five-year-old girl in South Carolina was put in hand cuffs for having a tantrum. Many different incidents, and those are just some of the ones we know of.

The way the children are treated, it’s as if they are preparing them for the school to prison pipeline. The way the children walk in formation; in line behind one another like in the prison. Going through the metal detector, the color, the layout, the formation of certain schools; it all resembles a prison. This starts at a very young age, and it starts with children who are black and brown. And I like to tell people that they will treat you like a child, but they will punish you like an adult. You know this is what the dominant side of society has been doing. Prison is the new cotton. “The cotton ain’t white no more, the cotton is brown.” And that’s the quote from Killer Mike, he said that in Elementary Genocide.

Corletha: Wow! That is so heavy! What role would you say that mental illness plays in the school to prison pipeline?

Rahiem: I am sure that some of these children and students are probably dealing with some type of depression and they are dealing with traumatic experiences in the neighborhoods and maybe even in their households. So, I think mental health plays a big part but unfortunately, you have more police officers in schools than you have psychologists and counselors. That is where the money is being spent, on custody and control. It’s not being spent on the wellbeing of the student. Not on a psychologist, or a school therapist, or someone who has their best interests at heart. You have a person that is not from your cultural background, and is seen as someone there to oppress you because you see what they do in the community. The police in the community is like an occupying army and we must be mindful that predominately school teachers are Caucasian females. 75% of them are Caucasian females. Out of that 75%, 25% are married to law enforcement officers. So, here it is you have the white female that mentally miseducates you and the white male that physically locks you up. That is the school to prison pipeline. I know when I say numbers like that, people are like come on, where did you get those numbers from? You can go online and do the research. And this is nothing new.

There was book that was written in the early 80’s, from and it’s called The Conspiracy to Destroy the Black Boy. There’s a part one and a part two. He talks about all of this back in the 80’s before many of y’all was born.

Corletha: Wow! I heard you make mention of psychology, school counselor, therapy and things of that nature. If you could advocate for any area of mental health to improve the outcome of the school to prison pipeline, what would it be and why?

Rahiem: In terms of mental health, one thing I would say is that I would never be an advocate of prescribing medication to children. Some of the children are not able to easily adapt to social environments and some learn differently. Medication is not going to speed up or fix that process. Recently in New York, four females, 12 years old are strip searched. They took a drug test on them because they thought the girls were high on drugs. [It was because] they were giddy and laughing. That’s what 12-year-old kids do. They violated their rights. They held them in the office, they made them strip and searched them for drugs. It was because they laughed. They are 12 years old. That is what they do, they laugh. There’s nothing wrong with laughter. It wouldn’t have happened if they were crying, like they made them do after they strip searched them. This is the society and the type of people that this generation is dealing with. So as far as mental health, I think the people in charge need the medicine and mental health services because if you can do that to a child, that is real telling of where society is headed. Yesterday the headline news, a bill is at its final stages of being signed, will allow teachers to carry firearms to school.

Corletha: Oh, my goodness!

Rahiem: So just imagine all the stuff that we have seen. The fights that we have seen, all the abuse on students by teachers, sexual abuse of students. Now, these same people will be allowed to carry guns. How does that play out? If the police officers and resource officers can’t stop mass shootings, what do you think a teacher going to do? Not to go off subject, there was recently a case of a teacher whose gun went off in class and he was recently arrested. Gun accidentally went off. Where he was at, you are not allowed to have a firearm on school grounds.

Corletha: I am definitely going to have to look into that, I didn’t realize the bill had made it that far.

Rahiem: Yeah, we are living in the era of Donald Trump. That shouldn’t surprise nobody. Doesn’t surprise me one bit.

Corletha: In your history as a film maker, you have had some pretty big names, whether known locally or internationally. People such as Dr. Kaba Kemene, Killer, Mike, Dr. Boyce Watkins, David Banner, Dr. Steve Perry to name a few. What do you contribute to building such strong partnerships and camaraderie in your industry?

Rahiem: A conversation. Pretty much I was doing the work before the documentary. So, reaching out and having a conversation. Some of them were familiar with the work that I do. Going into the prisons, talking and being an advocate for the voice of the voiceless. That allowed me to have a conversation with them and to check their availability. So, it wasn’t hard to get them. Some individuals I had a personal relationship.

More than anything, it’s really not about the big names. There are a lot of people who were relatively unknown in there, but they delivered. One individual is Tracey Syphax. He spoke big on reentry. He is an individual like myself, who was formerly incarcerated. We like to refer to ourselves as returning citizens. He is actually a multi-millionaire. He operates several different businesses where he employs individuals that come out of the penitentiary. He goes around the country teaching about entrepreneurship classes, doing workshops, and helping people get their businesses started. There is another individual; Professor Ed Garnes, a black psychiatrist that is doing phenomenal work. He teaches on the college level. He brought his work to the masses of people. We had Dr. Camilla Ali, a sister that teaches at Kent State University. She is phenomenal. She brought a lot of projects.

There are so many others. In addition to black educators, we had freedom fighters. We had Dhoruba al-Mujahid bin Wahad from the Panther 21. He did over 20 years in jail and was able to prove that he was targeted and framed by the city of New York and won a lawsuit against the city under the Show and Tell Program. We had our ancestor, our now ancestor, Dr. Frances Cress-Welsing. We had a host of people. I think with the last one, we ended it on a good note. I get emails and messages daily asking me when Elementary Genocide 4 is coming out. Unfortunately, there won’t be a 4 because these documentaries are not just documentaries. My motives were not just profit driven when I made it, they were solution orientated. I just feel like if you didn’t get it in 1, you should have gotten it in 2, if you didn’t get it in 2, you should have gotten it in 3. If you didn’t get it in the trilogy, then you were not trying to get the solution to the problem anyway.

Corletha: Ase. In addition to this work, you have a podcast called Necessary Blackness. What is the focus of your podcast and what are some topics that have been covered?

Rahiem: The focus of the podcast is to be an independent voice that speaks truth and power without using mainstream media. So, I can do a podcast on my own platform and I don’t have to worry about censorship. As many people know, I am the king of suspension on Facebook. I am currently suspended as we speak because of my political views. Certain things that I may say that are truthful and can be backed up with facts, rubs people the wrong way. It can make people uncomfortable, but I am not here to make people comfortable.

So, I think with the podcast, it’s an independent voice. It’s not about me, I like to bring in guests. People who are not necessarily heard in mainstream media and provide them with my platform. It’s just a celebration of black love and black culture. We have everybody on there from freedom fighters to community activists; stakeholders in the community. We talk about health, wellness, childhood trauma, polygamy, and black economic empowerment. The last episode that we just did was about why black love is a revolutionary act. We cover everything.

It’s called Necessary Blackness Podcast because this is a platform for melanated people by melanated people. You will never hear the voice of anybody else that is not black. I don’t care if it was John Brown fighting for the liberation of our people, he won’t be on Necessary Blackness Podcast. I don’t care, we will have another show for him.

Corletha: If someone wanted to tune in, how should they? How could they tune in?

Rahiem: We are on iTunes, Apple, Google Play, we are on Spotify. If you want to listen in your car, we are on Car Play. You can say, ‘Alexa, take me to Necessary Blackness Podcast’. We are on a lot of different platforms, you can just Google Necessary Blackness Podcast. Also, we are on YouTube under the same name. We are not hard to find.

Corletha: Alright. Every time I look up, it seems like you are on the road traveling somewhere. What is the purpose behind some of your trips and events that you are going to?

Rahiem: A lot of the traveling that I do is, for example the 10-city tour that I funded, that was free and open to the public. Just getting the word out there, educating the masses. I do a lot of community work where I go into the prisons and I speak to the inmates. You may see me traveling to another city or state to a prison to do a lecture. I visit colleges. Their black student organizations frequently call me out to do a speaking engagement. I do keynote speaking at several different colleges. I did the Race Awareness Week in Oregon at Southern Oregon University. I had several different days where I did prison bias training. I did Brother to Brother Land of Color Circle; we did community engagement. We did a screening of part one of Elementary Genocide and did a Q&A follow.

I also received an award in both 2016 and 2017. I spoke at Medgar Evers College, in Brooklyn. I went to Jacksonville FL. The city of Atlanta gave me a proclamation for National Reentry Month. That is something that I fund every year out of my own pocket, every June, National Reentry Month. I do that to give back to my community for the support that I have been given. I am not one of those Facebook activists typing keys. I act. If we don’t do it, no one else will either. I am an individual that likes to go out and speak to people and tell them not to look for these outside forces to be your leader. We need to take control of our own situation.

Corletha: Besides being a filmmaker, what are some other things that you do?

Rahiem: Besides being a filmmaker, I am currently working on a book that will be released soon. It is called Radical Hope in the 21st Century. Do we cling to our hope or cling to this fear? It is an anthology and it consists of myself and several individuals that I highly respect.

Corletha: You made mention to me behind the scenes about an investment. Can you tell me more about that?

Rahiem: Yes. I invested in an urban street wear company called Wingi. Wingi is a Swahili word that means abundant. Wingi is the line is for freedom fighters everywhere. A few brothers and sisters that pooled our money together and got behind this line. And everything happens in divine order. We wanted to go into another venture. When you are a truth seeker or speaker and you are working for someone else, you don’t have the job security you would have if you had our own stream of revenue. You could lose your job, as we see recently, if you say something that someone doesn’t like. So, I want to be able to fund my own movement and help others. We need to have our own money that comes from our own people to do that. Not money from outsiders. So this was one of the business ventures. We started formulating the ideas, logos and styles right around the time all the big white owned design companies such as Gucci and Prada were doing their black face things during black history month. You don’t have to wear Gucci anymore. You can rock Wingi Apparel. We never expected it to go as well as it has been, it has been a success thus far. We didn’t expect people to gravitate towards it as much as they have.

Corletha: What is your overall vision for your overall brand?

Rahiem: Well they say anything after ten years is an institution. I have been working on the micro level for well over 10 years. So now, I want to solidify my entertainment business and all ventures into a solid institution that can be carried on long after I am gone. I just want to leave a legacy for me, my family, and my supporters. I know there will be someone who will pick up the torch and carry on the tradition, because the fight is still going on.

Corletha: Ase. So how do you take care of yourself amongst all the things you do?

Rahiem: One thing is to make sure you take time away from social media. Sometimes I feel like I get more done when I am not always plugged in. Leave the digital world and be amongst family, friends, supporters and people who are genuine. For me, that is what keeps me grounded. Oh and keep yourself in the best health possible. You must eat right, plant based, vegan diet. I try to stick to it as much as possible; I am not perfect. But I stick to it about 90% of the time, I will live 90% longer than those partaking in McDonald’s and KFC.

Corletha: I want to thank you for your time.

Rahiem: Before we go, if anyone wants to get in touch with me, I am available on Facebook and IG and pretty much everywhere @Rahiemshabazz. I am an individual who answers my own dms and messages for anyone who wants to contact me.

No Comments

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.